|

LISTEN TO THIS THE AFRICANA VOICE ARTICLE NOW

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

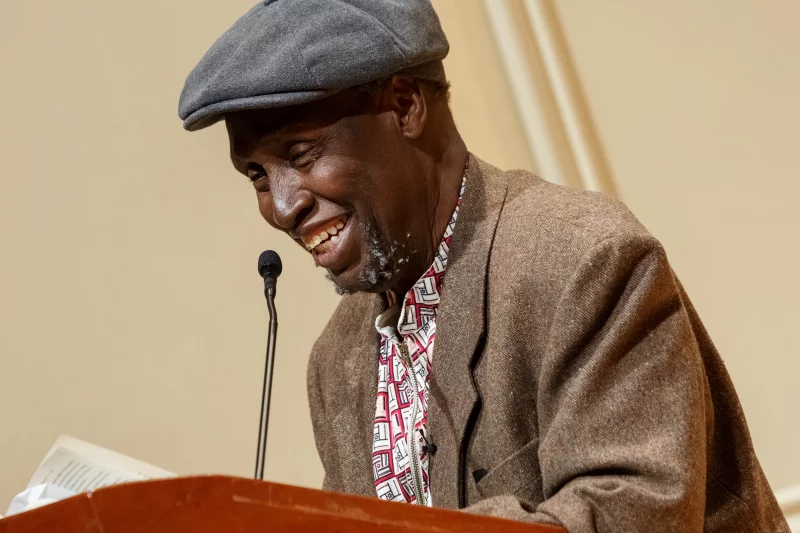

Years ago, a young boy sat under a mugumo tree in Kamiriithu, Limuru, listening to elders chant stories of Gikuyu heroes and ancient migrations. Around him, the soil had turned red with grief, colonial dispossession, Mau Mau arrests, and whispers of land stolen and never returned. That boy, one of 28 siblings from a father with four wives, would grow to become Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, the rebel with a pen, the conscience of a continent, and the man who dared to dream in his mother tongue.

On Wednesday, May 28, 2025, in Atlanta, Georgia, the boy who once stared down empires through fiction and philosophy passed away peacefully at the age of 87. The world, though brimming with tributes, feels suddenly quieter.

“He lived a full life, fought a good fight,” wrote his daughter, Wanjiku wa Ngũgĩ, echoing a sentiment known too well by those who followed his trailblazing journey.

The family, in a statement, signed off with the Gikuyu phrase: Rîa ratha na rîa thŭa. Tŭrî aira!; “With joy and sorrow. We are proud.”

And proud they must be. For few lives have so stubbornly, so poetically, insisted on the dignity of African memory.

From Exile to Existence

Ngũgĩ’s literary life didn’t begin with acclaim. It began with grief. The trauma of colonial rule, the loss of his brothers to the anti-colonial struggle, and the disintegration of his family under British brutality became the fertile ground from which his stories sprouted.

At 26, he published Weep Not, Child, the first novel in English by an East African. It was a cry against silence, and a whisper to the world that Africa would not be written off. But it was also the beginning of his eventual break from English itself.

The turning point came in 1977. Ngaahika Ndeenda (I Will Marry When I Want), a radical play co-authored in Gikuyu and staged by villagers at Kamiriithu, became a spark too bold for the Kenyan regime. For the crime of awakening the grassroots, Ngũgĩ was arrested and held in Kamĩtĩ Maximum Security Prison for a year, without charge. He emerged a different man: defiant, transformed, and resolved to write exclusively in African languages.

“In prison,” he later said, “I began to think in a more systematic way about language. Why was I not detained before, when I wrote in English?”

His answer was lifelong. From Caitaani Mũtharaba-Inĩ to Mũrogi wa Kagogo (Devil on the Cross to Wizard of the Crow), Ngũgĩ’s pen danced to the rhythm of Gikuyu, insisting that language is not just a medium, but it is memory, culture, and resistance.

Forced into exile in the early 1980s, Ngũgĩ carried Kenya in his bones. London. New York. California. He taught, lectured, debated, and always, always wrote. At UC Irvine, he helped found the International Center for Writing and Translation, opening the doors for other marginalised voices.

When he finally returned to Kenya in 2004, after 22 years away, the joy was short-lived. Armed intruders attacked him and his wife, Njeeri. But even this violence couldn’t erase his will. “Resistance,” he once said, “is how we stay alive.”

A Global Griot

Ngũgĩ was a regular contender for the Nobel Prize in Literature, often mentioned with hushed awe. He never won it. But history may yet find the Nobel unworthy of him.

His 2021 nomination for the International Booker Prize, for The Perfect Nine, an epic poem written in Gikuyu and translated by himself, marked a moment of poetic justice. At 83, he was still breaking boundaries.

But Ngũgĩ’s impact was never just about novels or awards. It was about a revolution of thought. At the University of Nairobi, he led a movement to decolonize the curriculum, demanding that African students read Achebe before Aristotle, and that African literature not be a footnote in its own land.

Ngũgĩ leaves behind nine children, many of them writers, academics, and cultural torchbearers; including Tee Ngũgĩ, Mukoma wa Ngũgĩ, Nducu wa Ngũgĩ, and Wanjiku wa Ngũgĩ. Through them, and through generations of students, readers, and freedom dreamers, his voice lives on.

His funeral and memorial arrangements will be shared in the coming days. But long before that, Africa, and the world, began the work of remembrance. Because Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o didn’t just write books. He wrote freedom into being.

And even now, in his absence, we hear him say:

“If you know all the languages of the world and you don’t know your mother tongue or the language of your culture, that is enslavement. On the other hand, if you know your mother tongue or the language of your culture and you add all the languages of the world to it, that is empowerment. And I believe in Kenya we should empowerment rather than enslavement.”

LEAVE A COMMENT

You must be logged in to post a comment.