|

LISTEN TO THIS THE AFRICANA VOICE ARTICLE NOW

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

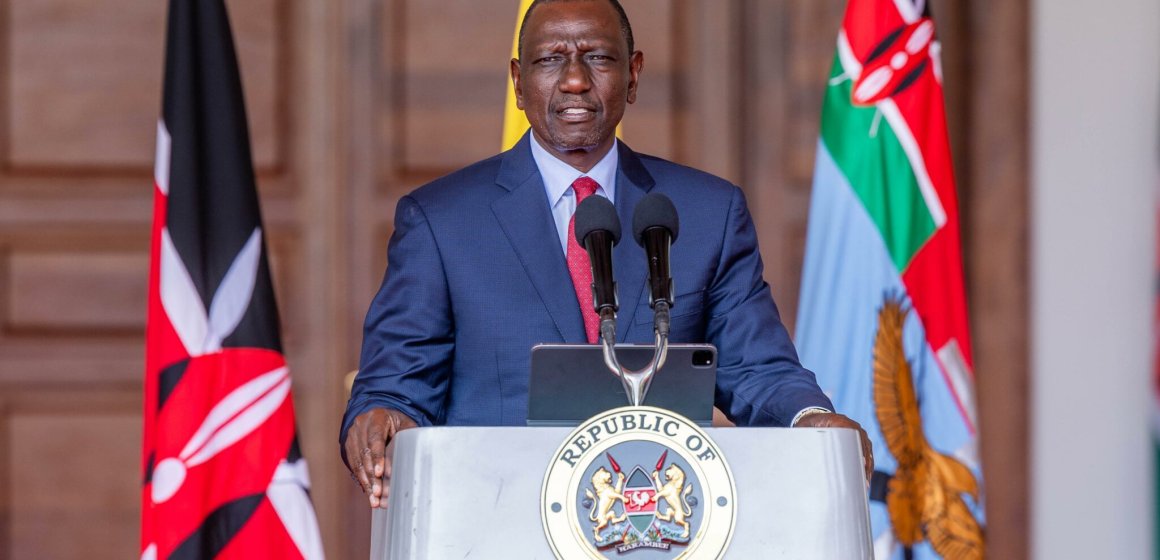

At a moment thick with the scent of incense and diplomacy, Kenya’s President William Ruto stood before an audience at the national prayer breakfast on Wednesday, May 28th, and chose words that were both rare and revealing.

“To our neighbours from Tanzania,” he said slowly, “if we have wronged you in any way, forgive us.”

There was no prompt from his official speech. No state statement had prepared the public. The apology was as unexpected as it was significant, an olive branch extended in the middle of rising heat, amid an online inferno that had outpaced diplomatic caution.

“For anything that Kenyans have done that is not right,” the president added, “we want to apologise.”

This was a turning point in a rapidly escalating diplomatic spat between Kenya and Tanzania, one that had started with the detention and alleged torture of activists, but quickly metastasized into a social media war and a broader continental conversation about sovereignty, solidarity, and digital citizenship.

The Spark That Lit the Fire

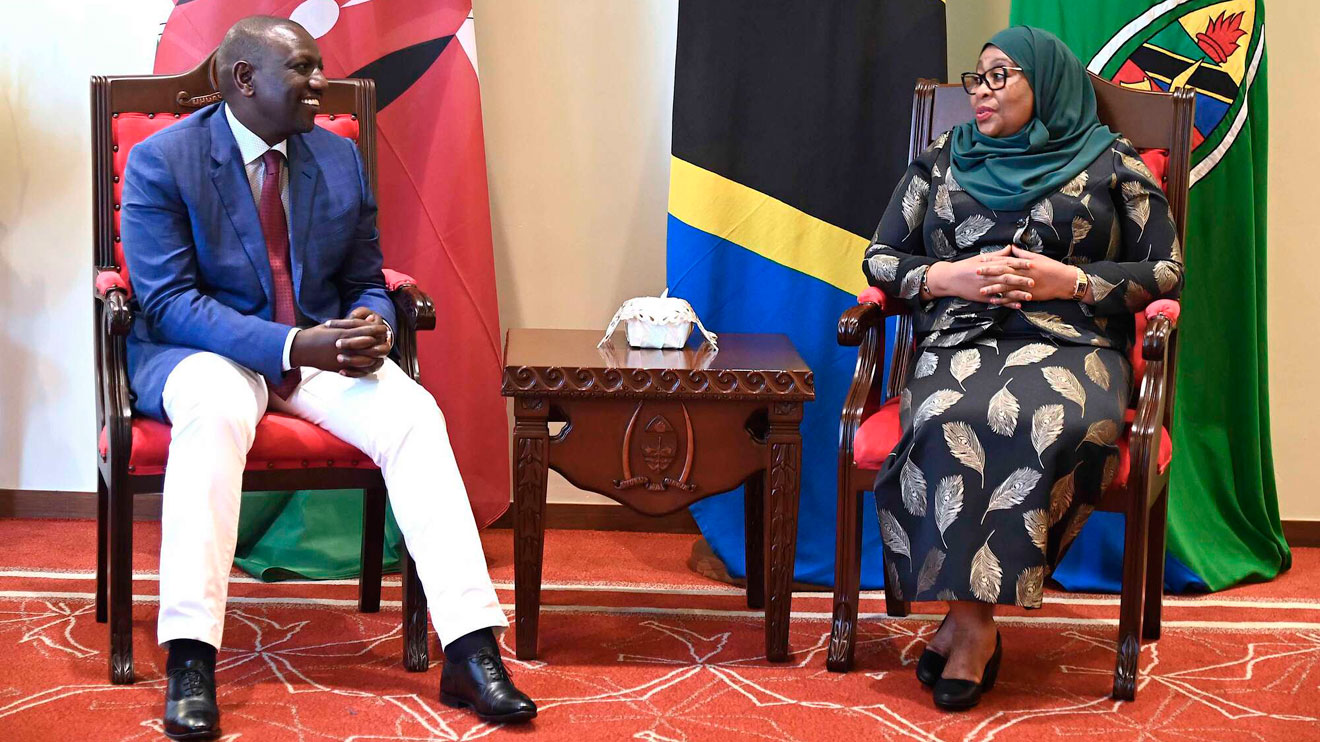

Just a week before Ruto’s apology, Tanzanian authorities had detained and deported prominent East African activists, including Kenya’s Boniface Mwangi and Uganda’s Agather Atuhaire. They had travelled to Dar es Salaam to attend the trial of opposition leader Tundu Lissu, a figure long at odds with Tanzanian President Samia Suluhu Hassan’s government.

According to Mwangi and Atuhaire, they were held incommunicado and tortured before being dumped at the border. “We were beaten, denied sleep, interrogated, and left at the Namanga border like criminals,” Mwangi wrote on X. International rights groups condemned the incident, calling it a violation of both human rights and regional cooperation.

But it was not just governments that reacted.

Online, young Kenyans, Gen-Zs armed with smartphones and sharp political wit, took to social media to denounce the arrests. Some of the posts were piercing, laced with humour and fury. But others strayed into the territory of national insult. President Samia became a frequent target.

By Monday, Tanzanian lawmakers were fuming.

“We have been cyberbullied. Our sovereignty has been disrespected,” Iringa Town MP Jesca Msambatavangu told Parliament, her voice rising above the chamber’s din. “Let Kenyans stop meddling in our domestic affairs.”

She wasn’t alone. Parliamentarians decried what they saw as digital hostility, an invasion not by guns or diplomats, but by memes and digital drama. Some MPs had their personal numbers leaked. Msambatavangu herself received so many WhatsApp messages from Kenyan citizens that she had to turn off her phone. Still, she struck a surprising note of openness.

“Kenyans are our neighbours, our brothers,” she said. “We cannot ignore each other.”

She even invited dialogue, suggesting the creation of a WhatsApp group for live discussion. “Let’s counter ideas with ideas,” she said.

Behind the Curtain of Apology

President Ruto’s words came in response to visiting American preacher Rickey Allen Bolden’s call for national and regional reconciliation. Yet they also addressed a growing domestic challenge. Kenya’s Gen-Z, the same demographic that had flamed Tanzania online, has also become Ruto’s fiercest internal critic, especially after last year’s deadly anti-tax protests.

“To our young people,” Ruto added during his remarks, “if there is anything we have done wrong, we seek your forgiveness.”

But the apologies, both to Tanzanians and to Kenyan youth, were met with mixed reactions. Some Tanzanians welcomed the gesture, others remained skeptical. Meanwhile, many Kenyan Gen-Zs dismissed the move as too little, too late.

“He should resign, not apologise,” one user posted on TikTok.

Tanzania has yet to officially respond to Kenya’s apology. President Samia had previously warned that she would not allow foreigners to “meddle” and cause “chaos” in the country. Her statement stood firm, even as regional pressure mounted.

Kenya and Uganda had lodged formal protests, accusing Tanzanian authorities of ignoring consular requests and violating international norms. But on the ground, or rather, online, it was the youth who shaped the narrative, applying a new kind of pressure no ambassador can replicate.

The apology may not end the diplomatic unease. It certainly won’t erase the memory of activists’ bruises or politicians’ flooded inboxes. But it opens a path, narrow, necessary, toward healing and dialogue.

LEAVE A COMMENT

You must be logged in to post a comment.